Pascal Molines does things his own way

Hot or not? The minimum requirements for being hot in the world of pastry these days tend to be gathering a large group of online followers and being inspired by flavours and ingredients from all over the world. Pastry chef and MOF Pascal Molines finds the second of these requirements interesting, but is completely indifferent to social media.

A fellow pastry chef like Cédric Grolet has eleven million followers on Instagram. Italian pastry chef Magrí Alberto has over five million. But this doesn’t bother Pascal Molines. ‘People who use social media are always trying to be better than someone else. This inevitably leads to excesses which aren’t necessarily commercial. Who would sell a croissant weighing one kilo? Or a cake with a diameter of two metres? It definitely looks nice and people talk about it online, but you can’t sell the product. That seems to me to be of highly doubtful value.’

Despite his invisibility on social media, Pascal Molines is definitely a well-known figure in the pastry world. He won the Coupe du Monde de la Pâtisserie in 1999 and gained a Meilleur Ouvrier de France (MOF) award a year later. Pascal enjoys passing on his expertise and has taught at the Paul Bocuse Institute in Lyon and Le Cordon Bleu Academy in Paris among other places. Moreover, he is a worldwide ambassador of French gastronomy. Shortly after the Covid pandemic, he opened his l’Atelier Sucré de Pascal in Anneyron, a small town just a stone’s throw from Lyon: a modest but excellent pastry shop which does a roaring trade especially at the weekend.

Molines distinguishes two separate areas in the pâtisserie sector. ‘If you have a shop, you make a cake and wait for the customer to come and get it. There are many factors that we can’t control, because the product is in the shop window for a while, then people take it home, present it in their own way and eat it at another point. As pastry chefs, we need stable products in such a situation that will last a long time so that we can minimise any negative effects of those factors and ensure that the customer can enjoy our products for a long time. If you work as a pastry chef in the catering industry, conditions are completely different. You can use any texture or flavour you want, because the guest is literally sitting there waiting for your dessert. You can display more creativity. In a shop, by contrast, people tend to choose the well-known classics in the range.’

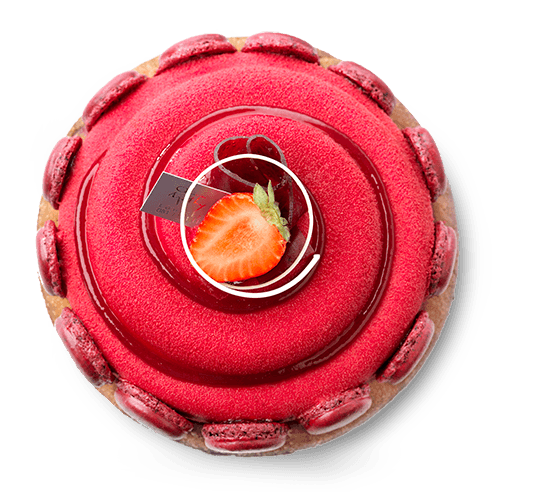

Frasian Style

That doesn’t mean that Pascal Molines never experiments – far from it! He takes an interest in the flavours and ingredients coming from Asia into French pâtisserie, for example. He visits Asia regularly and knows many Asian pastry chefs. ‘Some of them have been coming to France for fifty years to train here. The experience they gain in France at renowned establishments serves as a kind of diploma in their home country: it’s as if they’ve passed a certain test of competence when they’ve learnt the basics of pâtisserie in France.

Moreover, anything that comes from France has a luxury image in Asia. What goes for cognac, perfume and jewellery also applies to pâtisserie. Incidentally, the influences operate in both directions these days. In France we sometimes use typical Asian products to enhance our flavours, especially in desserts on a plate like yuzu, matcha or lemongrass. These unexpected flavours and lesser-known ingredients give our products a certain originality. We even refer to the Frasian style: an intriguing blend of French and Asian.’

Molines values craftsmanship, and as far as he is concerned, that doesn’t come from poring over videos on the Internet. ‘If you want to practise a profession, you don’t go to a Facebook page. Nothing can be achieved in five minutes. This profession requires countless skills and you learn new things every day. That goes for me too, even now! In this profession you can keep refining your approach. If you want to establish a successful business, you have to do everything yourself and ensure that everything goes through you. If you don’t, it won’t work.

We’ve ended up with a pastry sector in which many chefs have become assemblers instead of creators. They assemble their products with ready-made solutions, often because they don’t know how to make them themselves. There’s a big difference between seeing something and having done something. Nowadays people think: I’ve seen it, so I know how to do it. In a profession in which you have to work with your hands, that’s a serious misunderstanding.’

Molines believes that there is a risk that this could lead to flavours becoming blander. ‘Young people nowadays find products from some anonymous wholesaler acceptable. They’re less able to tell the difference from pastry from specialist shops, because they have never had the ingredients in their hands and haven’t tasted them before.’ Despite this, he thinks that consumers generally still know what is good. ‘Customers who come back to you for your croissants recognise quality. They notice the difference when something’s really good.

When I once did some consultancy work as an MOF, I was surprised by the large amount of ready-made lemon cream that is sold in buckets. To be honest, I didn’t even know that such a thing existed! A lemon tart should be a bit tangy, with a slight bitterness from the peel and a non-sticky Italian meringue that spreads over your entire palate. When you eat a good lemon tart, something happens to you, doesn’t it? You think: wow, this is delicious! You hear the crispy base, you taste the flavours in your mouth, you’re overwhelmed by the smell. That’s what makes pastry good. It can’t be that you just eat something and that’s it: something has to happen with all your senses.’

Try Pascal's ambassador recipes for Debic!

Discover new trends & preparations in this article!

Discover more